Western culture

Christianity

See also: Religious conversion and DivinizationThe word "enlightenment" is not generally used in Christian contexts for religious understanding or insight. More commonly used terms in the Christian tradition are religious conversion and revelation.Lewis Sperry Chafer (1871–1952), one of the founders of Dispensationalism, uses the word "illuminism". Christians who are "illuminated" are of two groups, those who have experienced true illuminism (biblical) and those who experienced false illuminism (not from the Holy Spirit).[65]Christian interest in eastern spirituality has grown throughout the 20th century. Notable Christians, such as Hugo Enomiya-Lassalle and AMA Samy, have participated in Buddhist training and even become Buddhist teachers themselves. In a few places Eastern contemplative techniques have been integrated in Christian practices, such as centering prayer.[web 24] But this integration has also raised questions about the borders between these traditions.[web 25]Western esotericism and mysticism

Western and Mediterranean culture has a rich tradition of esotericism and mysticism.[66] The Perennial philosophy, basic to the New Age understanding of the world, regards those traditions as akin to Eastern religions which aim at awakening/ enlightenment and developing wisdom. All mystical traditions possibly share a "common core",[67] a hypothesis which is central to New Age, but contested by a diversity of scientists like Katz and Proudfoot.[67]Judaism includes the mystical tradition of Kabbalah. Islam includes the mystical tradition of Sufism. In the Fourth Way teaching, enlightenment is the highest state of Man (humanity).[68]Nondualism[edit]

A popular western understanding sees "enlightenment" as "nondual consciousness", "a primordial, natural awareness without subject or object".[web 26] It is used interchangeably with Neo-Advaita.[web 27]This nondual consciousness is seen as a common stratum to different religions. Several definitions or meanings are combined in this approach, which makes it possible to recognize various traditions as having the same essence.[69] According to Renard, many forms of religion are based on an experiential or intuitive understanding of "the Real"[70]This idea of nonduality as "the central essence"[71] is part of a modern mutual exchange and synthesis of ideas between western spiritual and esoteric traditions and Asian religious revival and reform movements.[note 16] Western predecessors are, among others,New Age,[72] Wilber's synthesis of western psychology and Asian spirituality, the idea of a Perennial Philosophy, and Theosophy. Eastern influences are the Hindu reform movements such as Aurobindo's Integral Yoga and Vivekananda's Neo-Vedanta, the Vipassana movement, and Buddhist modernism. A truly syncretistic influence is Osho[73] and the Rajneesh movement, a hybrid of eastern and western ideas and teachings, and a mainly western group of followers.[74]Cognitive aspects

Religious experience as cognitive construct

"Religious experiences" have "evidential value",[75] since they confirm the specific worldview of the experiencer:[76][54][13]Yet, just like the very notion of "religious experience" is shaped by a specific discourse and habitus, the "uniformity of interpretation"[78] may be due to the influence of religious traditions which shape the interpretation of such "experiences".Various religious experiences

Yandell discerns various "religious experiences" and their corresponding doctrinal settings, which differ in structure and phenomenological content, and in the "evidential value" they present.[80] Yandell discerns five sorts:[81]- Numinous experiences - Monotheism (Jewish, Christian, Vedantic)[82]

- Nirvanic experiences - Buddhism,[83] "according to which one sees that the self is but a bundle of fleeting states"[84]

- Kevala experiences[85] - Jainism,[75] "according to which one sees the self as an undestructible subject of experience"[75]

- Moksha experiences[86] - Hinduism,[75] Brahman "either as a cosmic person, or, quite differently, as qualityless"[75]

- Nature mystical experience[85]

Cognitive science

Main articles: Cognitive science and Cognitive science of religionVarious philosophers and cognitive scientists state that there is no "true self" or a "little person" (homunculus) in the brain that "watches the show," and that consciousness is an emergent property that arise from the various modules of the brain in ways that are yet far from understood.[87][88][89] According to Susan Greenfield, the "self" may be seen as a composite,[90] whereas Douglas R. Hofstadter describes the sense of "I" as a result of cognitive process.[91]This is in line with the Buddhist teachings, which state thatTo this end, Parfit called Buddha the "first bundle theorist".[93]The idea that the mind is the result of the activities of neurons in the brain was most notably popularized by Francis Crick, the co-discoverer of DNA, in his book The Astonishing Hypothesis.[94][note 17] The basic idea can be traced back to at least Étienne Bonnot de Condillac. According to Crick, the idea was not a novel one:Entheogens

See also: EntheogenSeveral users of entheogens throughout the ages have claimed spiritual enlightenment with the use of these substances, their use and prevalence through history is well recorded, although subjected to harsh social taboos.In modern times we have seen a rise in this belief, for example Ayahuasca tourism, which is believed to be due to the rise of the information age. Older beliefs about these substances have been subject to scientific research, although halted in the 1970s, it has resumed again in the 1990s.Henosis

- For Ένωσις, the modern political movement to unify Greece and Cyprus, see Enosis.

- Henosis is also a synonym of Bulbophyllum, a genus of orchid.

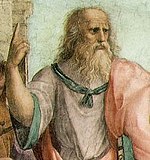

Part of a series on God Part of a series on Plato Plato from The School of Athens by Raphael, 1509Allegories and metaphors Related articles Henosis (Ancient Greek: ἕνωσις) is the word for mystical "oneness," "union," or "unity" in classical Greek.In Platonism, and especially Neoplatonism, the goal of henosis is union with what is fundamental in reality: the One (Τὸ Ἕν), the Source, or Monad.[1]The Neoplatonic concept has precedents in the Greek mystery religions[2] as well as parallels in Oriental philosophies.[3] It is further developed in the Corpus Hermeticum, in Christian theology, soteriology and mysticismand is an important factor in the historical development of monotheism during Late Antiquity. Usage in Classical texts and lexicon definition[edit]

The term is relatively common in classical texts, and has the meaning of "union" or "unity".[4]Divine work[edit]

See also: Greek hero cultTo get closest to the Monad, One, each individual must engage in divine work (theurgy) according to Iamblichus of Chalcis. This divine work can be defined as each individual dedicating their lives to making the created world and mankind's relationship to it, and one another, better. This is done by living a virtuous life seeking after one's Magnum opus. Under the teachings of Iamblichus (see the Egyptian Mysteries), one goes through a series of theurgy or rituals that unites the initiate to the Monad. These rituals mimic the ordering of the chaos of the Universe into the material world or cosmos. They also mimic the actions of the demiurge as the creator of the material world.The cosmos and order[edit]

Each individual as a microcosm reflects the gradual ordering of the universe referred to as the macrocosm. In mimicking the demiurge (divine mind), one unites with The One or Monad. Thus the process of unification, of "The Being," and "The One," is called Henosis. The culmination of Henosis is deification. Deification here making each man a god by unifying the concept of an external creator with themselves as creators, builders, craftmen of their own lives (one's life as their greatest work, their magnum opus), understanding the interdependence between the macro and microcosmic as the source of their activities. The divine unity here is a linearmodalistic emanation i.e. Monad, Dyad, Triad, etc.Fate and destiny[edit]

See also: CausalityAs is specified in the writings of Plotinus on Henology,[5][6] the highest stage of deification is tabula rasa, or a blank state where the individual may grasp or merge with The Source (or The One, this process being henosis or unity).[7][8] This absolute simplicity means that the nous or the person is then dissolved, completely absorbed back into the monad. Here within the Enneads of Plotinus the monad can be referred to as the Good above the demiurge.[9][10] The monad or dunamis (force) is of one singular expression (the will or the one is the good) all is contained in the Monad and the Monad is all (pantheism). All division is reconciled in the one, the final stage before reaching singularity, called duality (dyad), is completely reconciled in the Monad, Source or One (see monism). As the one, source or substance of all things the monad is all encompassing. As infinite and indeterminate all is reconciled in the dunamis or one. It is the demiurge or second emanation that is the nous in Plotinus. It is the demiurge (creator, action, energy) or nous that "perceives" and therefore causes the force (potential or One) to manifest as energy, or the dyad called the material world. Nous as being, being and perception (intellect) manifest what is called soul (World Soul).[11]Modalism[edit]

See also: emanationHenosis for Plotinus was defined in his works as a reversing of the ontological process of consciousness via meditation (in the Western mind to uncontemplate) toward no thought (Nous or demiurge) and no division (dyad) within the individual (being). Plotinus words his teachings to reconcile not only Plato with Aristotle but also various World religions that he had personal contact with during his various travels. Plotinus' works have an ascetic character in that they reject matter as an illusion (non-existent). Matter was strictly treated as immanent, with matter as essential to its being, having no true or transcendential character or essence, substance or ousia. This approach is called philosophical Idealism.[12]Divine unity by return[edit]

In Neoplatonic henology the individual is absorbed back into the primordial substance which is the substance (ousia) of all things, the uncaused cause. At the point of unity individuals become energy, and are then further reduced to force, potential (once they are stripped of their person, nous); the energy of individuals is then returned to the infinite non-sentient force—the Source or One—and reamalgamated back into the Universe.[13] The process then starts again and brings another part of the universe into line with theMonad (see Pantheism).[14][15] Hence the demiurge or creator is treated as an intrinsic (immanence) concept. The creator as category as divine mind, is the mind, therefore not outside the mind and is a construct called consciousness (nous) and does not objectively exist (per se). As nous or consciousness is but energy, activity in force. The actualization of things in potential. Potential can be called space, time as indeterminate, infinite, never ending. The demiurge or nous is the first sentience, a reflective duality that in the process of perpetual recurrence is man, himself. The monad, source or one is force, potential or dunamis it is the irrational or indeterminate vitality and is as irrational non-sentient. It is the substance of all things and that in its rich infinitiness reflected back on itself causing the demiurge, dyad, nous, as reflection or consciousness.[16]Within the works of Iamblichus, The One and reconciliation of division can be obtained through the process of theurgy. By mimicking the demiurge, the individual is returned to the cosmos to implement the will of the divine mind. Iamblichus used the rituals of the mystery religions to perform rituals on the individual to unite their outer and inner person. Thus one without conflict internal or external is united (henosis) and is The One (hen).Neoplatonism here is taking the concept of primordial unity (henosis) as rational and deterministic, emanating from indeterminism an uncaused cause. Since consciousness is an emanation it is not created nor is a caused cause per se. Unity (henosis) is no longer strictly rationalization (reconciliation) of man with being and becoming (ontology) but in the works of Neoplatonism considered also, salvation (soteriology).Jivanmukta

- This article is about the Hindu concept. For the yoga style, see Jivamukti Yoga.

Part of a series on Hindu philosophy Āstika Nāstika People Background[edit]

Jivanmukti i.e. freedom from the vicious cycle of birth and rebirth, is a concept in Hindu philosophy, particularly in the school of philosophy known as Advaita. The ultimate goal of Hinduism is liberation from the cycles of rebirth. This liberation is technically called moksha. In all schools of Hindu philosophy (except Advaita) liberation is necessarily an event beyond the experience of human beings. But the Advaita school of Shankaraenvisages that human beings are already liberated and the soul is already free - one has only to realise (and to accept) this freedom. Souls who have had this realisation are called jivanmuktas.Advaita view[edit]

Shankara explains that nothing can induce one to act who has no desire of his own to satisfy. The supreme limit of vairagya ("detachment"), is the non-springing of vasanas in respect of enjoyable objects; the non-springing of the sense of the “I” (in things which are the anatman) is the extreme limit of bodha ("awakening"), and the non-springing again of the modifications which have ceased is the extreme limit of Uparati("abstinence"). The Jivanmukta, by reason of his ever being Brahman, is freed from awareness of external objects and no longer aware of any difference between the inner atman and Brahman and between Brahman and the world, ever experiencing infinite consciousness, to him the world is as a thing forgotten. Vijnatabrahmatattvasya yathapurvam na samsrtih – "there is no samsara as before for one who has known Brahman".[1]There are three kinds of Prarabdha karma: Ichha ("personally desired"), Anichha ("without desire") and Parechha ("due to others' desire"). For a self realized person, a Jivanamukta, there is no Ichha-Prarabdha but the two others, Anichha and Parechha, remain,[2] which even a jivanmukta has to undergo.[2][3] According to the Advaita school for those of wisdom Prarabdha is liquidated only by experience of its effects; Sancita("accumulated karmas") and Agami ("future karmas") are destroyed in the fire of Jnana ("knowledge").[4]Implication[edit]

The Advaita school holds the view that the world appearance is owing to Avidya ("ignorance") that has the power to project i.e. to super-impose, the unreal on the real (Adhyasa), and also the power to conceal the real resulting in the delusion of the Jiva who experiences objects created by his mind and sees difference in this world, he sees difference between the atman ("the individual self") and Brahman ("the supreme Self"). This delusion caused by ignorance is destroyed when ignorance itself is destroyed by knowledge. When all delusion is removed there remains no awareness of difference. He who sees no difference is said to be a Jivanmukta. Perception of difference leads one from death to death, non-difference can be perceived only by the highly trained intellect, so states the Sruti (Katha Upanishad II.4.11).[5]Significance[edit]

The Advaita philosophy rests on the premise that noumenally the Absolute alone exists, Nature, Souls and God are all merged in the Absolute; the Universe is one, that there is no difference within it, or without it; Brahman is alike throughout its structure, and the knowledge of any part of it is the knowledge of the whole (Brihadaranyaka Upanishad II.4.6-14), and, since all causation is ultimately due to Brahman, since everything beside Brahman is an appearance, the Atman is the only entity that exists and nothing else. All elements emanated from the Atman (Taittiriya Upanishad II.1) and all existence is based on Intellect (Aitareya Upanishad III.3). The universe created by Brahman from a part of itself is thrown out and re-absorbed by the Immutable Brahman (Mundaka UpanishadI.1.7). Therefore, the Jiva (the individual self) is non-different from Brahman (the supreme Self), and the Jiva, never bound, is ever liberated. Through Self-consciousness one gains the knowledge of existence and realizes Brahman

Kama

For other meanings, see kama (disambiguation). For the Hindu god, see Kamadeva.

| |||||

| Kāma, in Hinduism, is one of the four goals of human life.[2] Above illustrate examples of kāma. | |||||

Kāma (Sanskrit, Pali; Devanagari: काम) means desire, wish, longing in Indian literature.[3] Kāma often connotes sexual desire and longing in contemporary literature, but the concept more broadly refers to any desire, wish, passion, longing, pleasure of the senses, the aesthetic enjoyment of life, affection, or love, with or without sexual connotations.[4][5]

Kāma is one of the four goals of human life in Hindu traditions.[2] It is considered an essential and healthy goal of human life when pursued without sacrificing the other three goals: Dharma (virtuous, proper, moral life), Artha (material prosperity, income security, means of life) and Moksha (liberation, release, self-actualization).[6][7] Together, these four aims of life are called Puruṣārtha.[8]

Definition and meaning[edit]

Kāma means “desire, wish or longing”.[3] In contemporary literature, kāma refers usually to sexual desire.[2] However, the term also refers to any sensory enjoyment, emotional attraction and aesthetic pleasure such as from arts, dance, music, painting, sculptor and nature.[1][9]

The concept kāma is found in some of the earliest known verses in Vedas. For example, Book 10 of Rig Veda describes the creation of the universe from nothing by the great heat. There in hymn 129, it states:

Brhadaranyaka Upanishad, one of the oldest Upanishads of Hinduism, uses the term kāma, also in a broader sense, as any desire:

Ancient Indian literature such as the Epics, that followed the Upanishads, develop and explain the concept of kāma together with Artha and Dharma. The Mahabharata, for example, provides one of the expansive definitions of kāma. The Epic claims kāma to be any agreeable and desirable experience (pleasure) generated by the interaction of one of five senses with anything congenial to that sense and while the mind is concurrently in harmony with the other goals of human life (dharma, artha and moksha).[13]

Kāma often implies the short form of the word kāmanā (desire, appetition). Kāma, however, is more than kāmanā. Kāma is an experience that includes the discovery of object, learning about the object, emotional connection, process of enjoyment and the resulting feeling of well being before, during and after the experience.[9]

Vatsyayana, the author of Kamasutra, describes kāma as happiness that is a manasa vyapara (phenomenon of the mind). Just like the Mahabharata, Vatsyayana's Kamasutra defines kāma as pleasure an individual experiences from the world, with one or more senses - hearing, seeing, tasting, smelling and feeling - in harmony with one’s mind and soul.[6] Experiencing harmonious music is kama, as is being inspired by natural beauty, the aesthetic appreciation of a work of art and admiring with joy something created by another human being. Kama sutra, in its discourse on kāma, describes many arts, dance and music forms, along with sex as means to pleasure and enjoyment.[13]

John Lochtefeld explains[2] kāma as desires, noting that it often refers to sexual desire in contemporary literature, but in ancient Indian literature kāma includes any kind of attraction and pleasure such as those from the arts.

Karl Potter describes[14] kama as an attitude and capacity. A little girl who hugs her teddy bear with a smile is experiencing kama, as are two lovers in embrace. During these experiences, the person connects and identifies the loved as part of oneself, feels more complete, fulfilled and whole by experiencing that connection and nearness. This, in the Indian perspective, is kāma.[14]

Hindery notes the inconsistent and diverse exposition of kāma in various ancient texts of India. Some texts, such as the Epic Ramayana, paint kāma through the desire of Rama for Sita, one that transcends the physical and marital into a love that is spiritual, and something that gives Rama his meaning of life, his reason to live.[15] Both Sita and Rama, frequently express their unwillingness and inability to live without the other.[16] This romantic and spiritual view of kāma in the Ramayana by Valmiki is quite different, claim Hindery[15] and others,[17] than the normative and dry description of kāma in the law codes of smriti by Manu for example.

Gavin Flood explains[18] kāma as “love” without violating dharma (moral responsibility), artha (material prosperity) and one’s journey towards moksha (spiritual liberation).

Kāma in Hinduism[edit]

In Hinduism, kāma is regarded as one of the four proper and necessary goals of human life (purusharthas), the others being Dharma (virtuous, proper, moral life), Artha (material prosperity, income security, means of life) andMoksha (liberation, release, self-actualization).[7][20]

Relative precedence between Kama, Artha, and Dharma[edit]

Ancient Indian literature emphasizes that dharma precedes and is essential. If dharma is ignored, artha and kama lead to social chaos.[21]

Vatsyayana in Kama Sutra recognizes relative value of three goals as follows: artha precedes kama, while dharma precedes both kama and artha.[6] Vatsyayana, in Chapter 2 of Kama sutra, presents a series of philosophical objections argued against kama and then offers his answers to refute those objections. For example, one objection to kāma (pleasure, enjoyment), acknowledges Vatsyayana, is this concern that kāma is an obstacle to moral and ethical life, to religious pursuits, to hard work, and to productive pursuit of prosperity and wealth. The pursuit of pleasure, claim objectors, encourages individuals to commit unrighteous deeds, bring distress, carelessness, levity and suffering later in life.[22] These objections were then answered by Vatsyayana, with the declaration that kāma is as necessary to human beings as food, and kāma is holistic with dharma and artha.

Kama is necessary for existence[edit]

Just like good food is necessary for the well being of the body, good pleasure is necessary for healthy existence of a human being, suggests Vatsyayana.[23] A life without pleasure and enjoyment - sexual, artistic, of nature - is hollow and empty. Just like no one should stop farming crops even though everyone knows herds of deer exist and will try to eat the crop as it grows up, in the same way claims Vatsyayana, one should not stop one's pursuit of kāma because dangers exist. Kama should be followed with thought, care, caution and enthusiasm, just like farming or any other life pursuit.[23]

Vatsyayana's book the Kama Sutra, in parts of the world, is presumed or depicted as a synonym for creative sexual positions; in reality, only 20% of Kama Sutra is about sexual positions. The majority of the book, notes Jacob Levy,[24] is about the philosophy and theory of love, what triggers desire, what sustains it, how and when it is good or bad. Kama Sutra presents kama as an essential and joyful aspect of human existence.[25]

Kama is holistic[edit]

| Part of a series on |

| Love |

|---|

Vatsyayana claims kama is never in conflict with dharma or artha, rather all three coexist and kama results from the other two.[6]

Pleasure in general, sexual pleasure in particular, is neither shameful nor dirty, in Hindu philosophy. It is necessary for human life, essential for well being of every individual, and wholesome when pursued with due consideration of dharma and artha. Unlike the precepts of some religions, kāma is celebrated in Hinduism, as a value in its own right.[27] Together with artha and dharma, it is an aspect of a holistic life.[9][28] All threepurusharthas - Dharma, Artha and Kama - are equally and simultaneously important.[29]

Kama and stage of life[edit]

Some[6][30] ancient Indian literature observe that the relative precedence of artha, kama and dharma are naturally different for different people and different age groups. In a baby or child, education and kāma (artistic desires) take precedence; in youth kāma and artha take precedence; while in old age dharma takes precedence.

Kama as deity[edit]

Kāma is personified as deity Kamadeva and his consort Rati. Deity Kama is comparable to the Greek deity Eros - they both trigger human sexual attraction and sensual desire.[2][8] Kama rides a parrot, and the deity is armed with bow and arrows to pierce hearts. The bow is made of sugarcane stalk, the bowstring is a line of bees, and the arrows are tipped with five flowers representing five emotions-driven love states.[31] The five flowers on Kama arrows are lotus flower (infatuation), ashoka flower (intoxication with thoughts about the other person), mango flower (exhaustion and emptiness in absence of the other), jasmine flower (pinning for the other) and blue lotus flower (paralysis with confusion and feelings). Kama is also known as Ananga (literally "one without body") because desire strikes formlessly, through feelings in unseen ways.[2] The other names for deity Kama include Madan (he who intoxicates with love), Manmatha (he who agitates the mind), Pradyumna (he who conquers all) and Kushumesu (he whose arrows are flowers).[32]

Kama in Buddhism[edit]

In Buddhism's Pali Canon, the Gautama Buddha renounced (Pali: nekkhamma) sensuality (kāma) in route to his Awakening.[33] Some Buddhist lay practitioners recite daily the Five Precepts, a commitment to abstain from "sexual misconduct" (kāmesu micchācāra).[34] Typical of Pali Canon discourses, the Dhammika Sutta (Sn 2.14) includes a more explicit correlate to this precept when the Buddha enjoins a follower to "observe celibacy or at least do not have sex with another's wife."[35]

Theosophy: kama, kamarupa and kamaloka[edit]

In the Theosophy of Blavatsky, Kama is the fourth principle of the septenary, associated with emotions and desires, attachment to existence, volition, and lust.[36]

Kamaloka is a semi-material plane, subjective and invisible to humans, where disembodied "personalities", the astral forms, called Kama-rupa remain until they fade out from it by the complete exhaustion of the effects of the mental impulses that created theseeidolons of human and animal passions and desires. It is associated with Hades of ancient Greeks and the Amenti of the Egyptians, the land of Silent Shadows; a division of the first group of the Trailõkya.

Salvation

For other uses, see Salvation (disambiguation).

| Part of a series on |

| Salvation |

|---|

|

| General concepts |

| Particular concepts |

| Punishment |

| Reward |

Salvation (Latin salvatio; Greek sōtēria; Hebrew yeshu'ah) is being saved or protected from harm[1] or being saved or delivered from some dire situation.[2] In religion, salvation is stated as the saving of the soul from sin and its consequences.[3]

The academic study of salvation is called soteriology. It concerns itself with the comparative study of how different religious traditions conceive salvation (a concept existing across a wide range of cultural traditions), and how they believe it is obtained.

Meaning

In religion, salvation is the saving of the soul from sin and its consequences.[4] It may also be called "deliverance" or "redemption" from sin and its effects.[5] Salvation is considered to be caused either by the free will and grace of a deity or by personal efforts through prayer and asceticism, or some combination of the two. Religions often emphasize the necessity of both personal effort—for example, repentance and asceticism—and divine action (e.g. grace).

Abrahamic religions[edit]

Judaism[edit]

See also: Atonement in Judaism

In contemporary Judaism, redemption (Hebrew ge'ulah), refers to God redeeming the people of Israel from their various exiles.[6] This includes the final redemption from the present exile.[7]

Judaism holds that adherents do not need personal salvation as Christians believe. Jews do not subscribe to the doctrine of Original sin.[8] Instead, they place a high value on individual morality as defined in the law of God — embodied in what Jews know as theTorah or The Law, given to Moses by God on Mount Sinai, the summary of which is comprised in the Ten Commandments. The Jewish sage Hillel the Elder states that The Law can be further compressed in just one line, popularly known as the Golden Rule: "That which is hateful to you, do not do unto your fellow".[9]

In Judaism, salvation is closely related to the idea of redemption, a saving from the states or circumstances that destroy the value of human existence. God as the universal spirit and Creator of the World, is the source of all salvation for humanity, provided an individual honours God by observing his precepts. So redemption or salvation depends on the individual. Judaism stresses that salvation cannot be obtained through anyone else or by just invoking a deity or believing in any outside power or influence.[9]

When examining Jewish intellectual sources throughout history, there is clearly a spectrum of opinions regarding death versus the Afterlife. Possibly an over-simplification, one source says salvation can be achieved in the following manner: Live a holy and righteous life dedicated to Yahweh, the God of Creation. Fast, worship, and celebrate during the appropriate holidays.[10] By origin and nature, Judaism is an ethnic religion. Therefore, salvation has been primarily conceived in terms of the destiny of Israel as the elect people of Yahweh (often referred to as “the Lord”), the God of Israel.[7] In the biblical text of Psalms, there is a description of death, when people go into the earth or the "realm of the dead" and cannot praise God. The first reference to resurrection is collective in Ezekiel's vision of the dry bones, when all the Israelites in exile will be resurrected. There is a reference to individual resurrection in the Book of Daniel (165 BCE), the last book of the Hebrew Bible.[11] It was not until the 2nd century BCE that there arose a belief in an afterlife, in which the dead would be resurrected and undergo divine judgment. Before that time, the individual had to be content that his posterity continued within the holy nation.[7]

The salvation of the individual Jew was connected to the salvation of the entire people. This belief stemmed directly from the teachings of the Torah. In the Apostle Paul's letter to the Romans,[Romans 9-11] the notion of corporate salvation of Israel is reflected. In the Torah, God taught his people sanctification of the individual. However, he also expected them to function together (spiritually) and be accountable to one another. The concept of salvation was tied to that of restoration for Israel.[12]

Christianity[edit]

Main articles: Salvation (Christianity) and Atonement in Christianity

Christianity’s primary premise is that the incarnation and death of Jesus Christ formed the climax of a divine plan for humanity’s salvation. This plan was conceived by God consequent on the Fall of Adam, the progenitor of the human race, and it would be completed at the Last Judgment, when the Second Coming of Christ would mark the catastrophic end of the world.[13]

For Christianity, salvation is only possible through Jesus Christ. Christians believe that Jesus' death on the cross was the once-for-all sacrifice that atoned for the sin of humanity.[13]

The Christian religion, though not the exclusive possessor of the idea of redemption, has given to it a special definiteness and a dominant position. Taken in its widest sense, as deliverance from dangers and ills in general, most religions teach some form of it. It assumes an important position, however, only when the ills in question form part of a great system against which human power is helpless.[14]

According to Christian belief, sin as the human predicament is considered to be universal.[15] For example, in Romans 1:18-3:20 the Apostle Paul declared everyone to be under sin—Jew and Gentile alike. Similarly, theApostle John was explicit: "If we say that we have no sin, we deceive ourselves and the truth is not in us".[1 Jn. 1:8] Again, he said, "Should we say that we have not sinned, we make him a liar and his word is not in us".[1:10]Salvation is made possible by the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus, which in the context of salvation is referred to as the "atonement".[16] Christian soteriology ranges from exclusive salvation[17]:p.123 to universal reconciliation[18] concepts. While some of the differences are as widespread as Christianity itself, the overwhelming majority agrees that salvation is made possible by the work of Jesus Christ, the Son of God, dying on the cross.

Variant views on salvation are among the main fault lines dividing the various Christian denominations, both between Roman Catholicism and Protestantism and within Protestantism, notably in the Calvinist–Arminian debate, and the fault lines include conflicting definitions of depravity, predestination, atonement, but most pointedly justification.

Salvation is believed to be a process that begins when a person first becomes a Christian, continues through that person's life, and is completed when they stand before Christ in judgment. Therefore, according to Catholic apologist James Akin, the faithful Christian can say in faith and hope, "I have been saved; I am being saved; and I will be saved."[20]

Christian salvation concepts are varied and complicated by certain theological concepts, traditional beliefs, and dogmas. Scripture is subject to individual and ecclesiastical interpretations. While some of the differences are as widespread as Christianity itself, the overwhelming majority agrees that salvation is made possible by the work of Jesus Christ, the Son of God, dying on the cross.

The purpose of salvation is debated, but in general most Christian theologians agree that God devised and implemented his plan of salvation because he loves them and regards human beings as his children. Since human existence on Earth is said to be "[given] to sin",[Jn 8:34] salvation also has connotations that deal with the liberation[21] of human beings from sin, and the suffering associated with the punishment of sin—i.e., "the wages of sin is death."[Rom. 6:23]

Christians believe that salvation depends on the grace of God. Stagg writes that a fact assumed throughout the Bible is that humanity is in "serious trouble from which we need deliverance…. The fact of sin as the human predicament is implied in the mission of Jesus, and it is explicitly affirmed in that connection". By its nature, salvation must answer to the plight of humankind as it actually is. Each individual's plight as sinner is the result of a fatal choice involving the whole person in bondage, guilt, estrangement, and death. Therefore, salvation must be concerned with the total person. "It must offer redemption from bondage, forgiveness for guilt, reconciliation for estrangement, renewal for the marred image of God".[22]

Islam[edit]

In Islam, salvation refers to the eventual entrance to heaven. Islam teaches that people who die disbelieving in the God do not receive salvation. It also teaches that non-Muslims who die believing in the God but disbelieving in his message (Islam), are left to his will. Those who die believing in the One God and his message (Islam) receive salvation.[23]

Narrated Anas Radeyallāhu ′Anhu that Muhammad Ṣallallāhu ′alayhe wa sallam said,

Islam teaches that all who enter into Islam must remain so in order to receive salvation.

For those who have not been granted Islam or to whom the message has not been brought;

Tawhid[edit]

See also: Tawhid and Shirk (Islam)

Belief in the “One God”, also known as the Tawhid (التَوْحيدْ) in Arabic, consists of two parts (or principles):

- Tawheedo Al Ruboobeeya ( تَوْحيدُ الرُبوبِيَّة): Believing in the attributes of God and attributing them to no other but God. Such attributes include Creation, having no beginning, and having no end. These attributes are what make a God. Islam also teaches 99 names for God, and each of these names defines one attribute. One breaks this principle, for example, by believing in an Idol as an intercessor to God. The idol, in this case, is thought of having powers that only God should have, thereby breaking this part of Tawheed. No intercession is required to communicate with, or worship, God.[25]

- Tawheedo Al Ilooheeya (تَوْحيدُ الإِلوهيَّة): Directing worship, prayer, or deed to God, and God only. For example, worshiping an idol or any saint or prophet is also considered Shirk, though prophets and saints may be asked for guidance or to pray for them.

Sin and repentance[edit]

See also: Repentance in Islam and Islamic views on sin

Islam also stresses that in order to gain salvation, one must also avoid sinning along with performing good deeds. Islam acknowledges the inclination of humanity towards sin.[26][27] Therefore, Muslims are constantly commanded to seek God's forgiveness and repent. Islam teaches that no one can gain salvation simply by virtue of their belief or deeds, instead it is the Mercy of God, which merits them salvation.[28] However, this repentance must not be used to sin any further. Islam teaches that God is Merciful, but it also teaches that He is Omnipresent. The Quran states:

Islam describes a true believer to have Love of God and Fear of God. Islam also teaches that every person is responsible for their own sins. The Quran states;

Al-Agharr al-Muzani, a companion of Mohammad, reported that Ibn 'Umar stated to him that Mohammad said,

Sin in Islam is not a state, but an action (a bad deed); Islam teaches that a child is born sinless, regardless of the belief of his parents, dies a Muslim; he enters heaven, and does not enter hell. Sahih al-Bukhari, 2:23:467

Five Pillars[edit]

Main article: Five Pillars of Islam

There are acts of worship that Islam teaches to be mandatory. Islam is built on five principles. Narrated Ibn 'Umar that Muhammad said,

Not performing the mandatory acts of worship may deprive Muslims of the chance of salvation.[32]

Indian religions[edit]

Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism and Sikhism share certain key concepts, which are interpreted differently by different groups and individuals.[33] In those religions one is not liberated from sin and its consequences, but from the cycle of rebirth which is perpetuated by the passions and delusions, and its resulting actions.[34] They differ however on the exact nature of this liberation.[34] Salvation is called moksha[34] or mukti which mean liberation and release respectively. This state and the conditions considered necessary for its realization is described in early texts of Indian religion such as the Upanishads and the Pali Canon, and later texts such the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali and the Vedanta tradition.[35] Moksha can be attained by practicing Sādhanā, literally "a means of accomplishing something".[36] It includes a variety of disciplines, such as yoga and meditation.

Nirvana is the profound peace of mind that is acquired with moksha (liberation). In Buddhism and Jainism, it is the state of being free from suffering. In Hindu philosophy, it is union with the Brahman (Supreme Being). The word literally means "blown out" (as in a candle) and refers, in the Buddhist context, to the blowing out of the fires of desire, aversion, and delusion,[37][38] and the imperturbable stillness of mind acquired there-after.[37]

In Theravada Buddhism the emphasis is on one's own liberation from samsara.[38] The Mahayana traditions emphasize the Bodhisattva-path,[38] in which "each Buddha and Bodhisattwa is a redeemer", assisting the Buddhist in seeking to achieve the redemptive state.[39] The assistance rendered is a form of self-sacrifice on the part of the teachers, who would presumably be able to achieve total detachment from worldly concerns, but have instead chosen to remain engaged in the material world to the degree that this is necessary to assist others in achieving such detachment.[39] Other disciplines are not so desolate, and "each Buddha and Bodhisattwa is a redeemer", assisting the Buddhist in seeking to achieve the redemptive state.

No comments:

Post a Comment